Boxwood has been used as a component of holiday décor for close to 200 years in North America.The long-lasting, evergreen foliage is perfect for garlands, swags, centerpieces, mantle decorations, and the ever-popular wreath.

A classic, simple boxwood wreath will last well into the New Year. Design and photo: Annie Saunders.

Wreaths can be boxwood-only (farmhouse-style), or added to other mixed greenery such as holly, juniper, fir, pine, cedar, magnolia, etc. Any healthy boxwood species or cultivars will do! For variation - if you’ve got access to any Buxus harlandii species or cultivars such as ‘Richard’, the glossy, elongated leaves are especially interesting. Also consider B. microphylla ‘John Baldwin’ and B. sempervirens ‘Fastigiata’ - both have blue-green cast to the foliage. A few sprigs of cream or gold variegated boxwood such as B. sempervirens ‘Elegantissima’ or B. microphylla ‘Golden Dream’ really lights up the piece.

Here’s a florist’s trick to keep the boxwood fresher, longer: submerge/soak the pieces in water for up to 12 hours. Allow to dry, then apply an antidessicant/antitranspirent product such as Wilt Pruf - either to the pieces or the finished wreath. As with everything else DIY, there are oodles of YouTube videos that demonstrate wreath construction - the process of wiring or otherwise securing the boxwood pieces and other décor to wire, foam, or vine wreath forms.

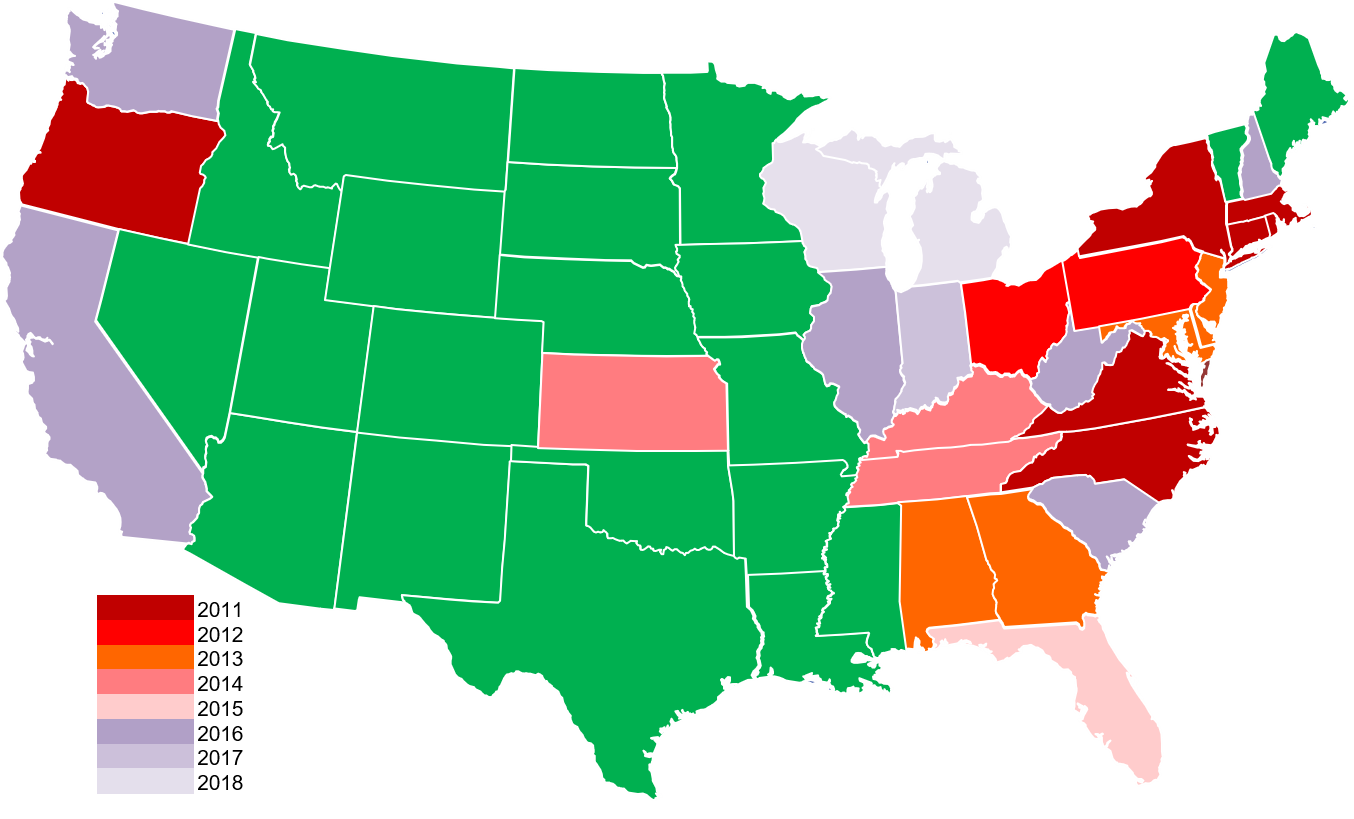

Let’s repeat an important point mention previously: healthy boxwood. If not properly handled, infected holiday greenery can introduce boxwood blight (Calonectria pseudonaviculata) to areas not previously impacted. If you’re not taking your own cuttings, try to purchase greenery from a reputable nursery, preferably in a state blight compliance/cleanliness program (see state Department of Agriculture listings). Inspect carefully for any signs of boxwood blight (visit https://www.newgenboxwood.com/boxwood-blight-1#identify for photos of symptoms). Fungal spore structures can persist throughout cold weather. The main objective is to prevent contact of any potentially infected material with boxwood in the surrounding landscape. To minize risk even with clean-looking material, be sure to follow boxwood blight BMPs for disposal - double bag and send to the landfill. Do not compost or add to your brushpile. Sanitize pruners or shears used after shaping your décor. Just a few simple steps will help keep your own boxwood safe while enjoying the classic beauty of boxwood for the holidays!

For inspiration, here’s a beautiful boxwood wreath created at the Saunders Brothers Farmers Market. Sprigs of Buxus sempervirens ‘Elegantissima’ and winterberry holly (Ilex verticillata ) are perfect accents - no bow required! Design and photo: Annie Saunders Burnett.