The Saunders Family

Growing up a Saunders predisposes you to have a certain affection towards boxwood. In our previous post we told the story of Paul Saunders and how he turned his passion for boxwood cultivation into a successful family business. Saunders Brothers Nursery began growing boxwood over 70 years ago and this was just the beginning. As the business has transitioned to a new generation of leadership, Paul’s sons, Robert, Bennett, Tom, and Jim reflect on their memories from sticking boxwood cuttings to earn an extra penny, to the discovery of Boxwood Blight in the United States and, to the creation of the NewGen™ program.

From an early age, the sons participated in every part of boxwood production around the farm. Bennett Saunders, General Manager of Saunders Genetics, remembers, “As kids, we would get paid a penny apiece for each boxwood cutting we stripped and stuck. This is how we would earn our extra spending money.” As the boys grew, they continued to play an essential part in the daily farm responsibilities. “I remember spending most weekday evenings at the nursery loading trucks with boxwood from March to May,” recalls Bennett. “At the time, boxwood were about 40% of the plants we grew.”

Boxwood Decline affecting English boxwood in a landscape

One of the first setbacks in boxwood production came about in the 1970s with the advent of Boxwood Decline. Up until this point, most of the boxwood market was made up of English boxwood (Buxus sempervirens ‘Suffruticosa’). As Boxwood Decline became more prevalent, the company began to move towards a wider selection of boxwood cultivars that were more resistant to the disease. Robert Saunders, General Manager of Saunders Brothers remembers, “In the spring of either 1981 or 1982, I was in high school and I got a note from the principal’s office saying I needed to call home. I called and my dad explained that he wanted me to come home to see an experiment he was doing. He was planting in an area just outside the yard at our house, a test garden of new varieties of boxwood. At that time, we grew only English and American boxwood, but my dad thought we should try some new ones.” Robert was dumbfounded for two reasons, “Number one, I hated plants, so I did not want to have anything to do with it. Number two, why did we need new varieties of boxwood? Little did I know I would end up working in the middle of it. From those trials, an evolution of perspective began and, we soon found Green Beauty, Green Velvet, Green Mountain and many other varieties. Most importantly it taught us about life beyond our small boxwood world.”

The exploration into new varieties of boxwood began to shed light on another lurking boxwood pest. “There was a field planting of Buxus sempervirens ‘Elizabeth Inglis’ that had just been eaten up with Boxwood Leafminer,” Bennett remembers. “It had never been sprayed and was just covered in blistered leaves.” Deciding this might be something worth exploring, they planted some other varieties near the host plant to see if different cultivars showed any natural resistance to the pest. Early observations showed that there was some hope for these different cultivars which encouraged Saunders to pursue more formal research.

Boxwood Leafminer larvae causing the boxwood leaves to swell and blister.

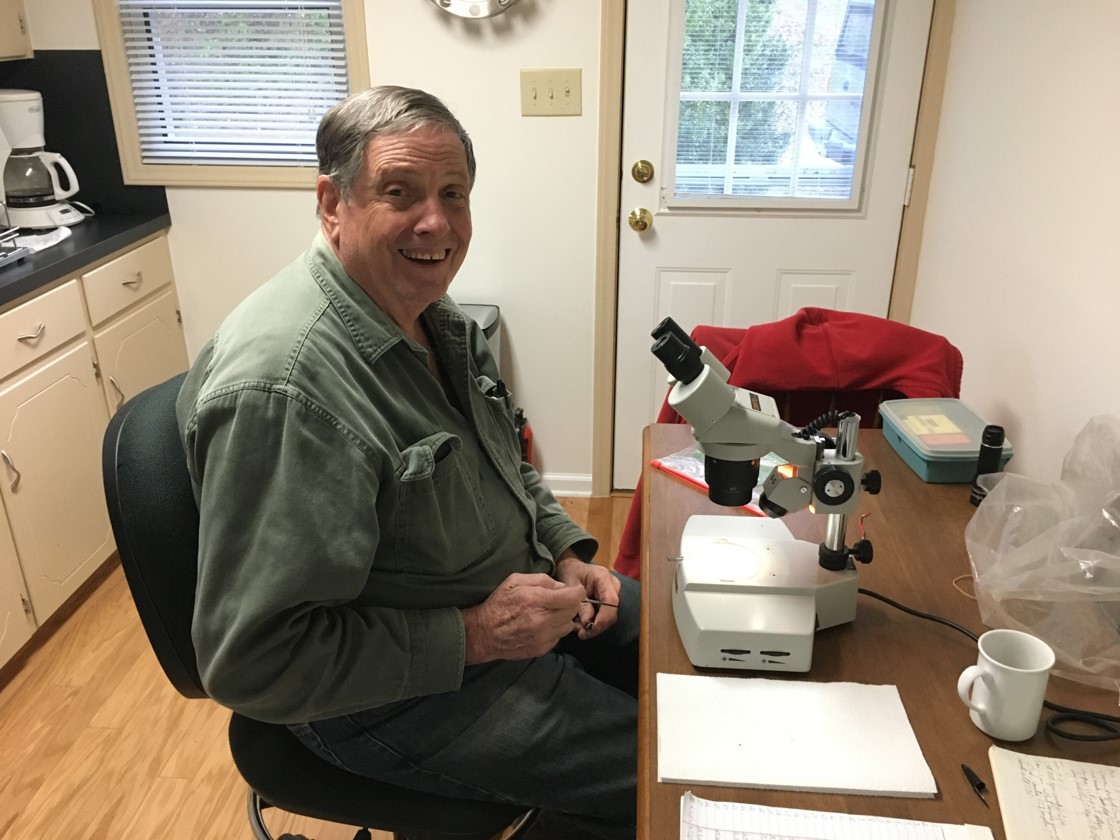

Dissecting boxwood leaves to count larvae.

In the early 2000s, Boxwood Leafminer incidences started to become more prevalent, coinciding with a general desire to reduce the use of pesticides, particularly the neonicotinoids. Saunders Brothers recruited retired nematologist Bob Dunn from the University of Florida to help them set up a replicated plot to collect data. They began by planting a test block where host plants infected with Leafminer were planted alongside many different cultivars of boxwood. Since the fall of 2006, thousands of leaf samples from the test area have been collected. Each leaf was dissected, and larvae were counted. The collection of this data over a decade showed a strong variation of cultivars’ natural resistance to Leafminer. This in turn meant a reduction in the use of pesticides and an increase in the value of boxwood in today’s gardens.

Bob Dunn, retired nematologist, working on Boxwood Leafminer research.

Boxwood Blight affecting a field nursery.

Then, in the fall of 2011, Bennett recalls that, “we began to hear horror stories about a disease called Boxwood Blight which was devastating boxwood nurseries in North Carolina and Connecticut. We called a meeting the Monday after Thanksgiving to decide what to do. We decided we needed to go to Europe before the MANTS show to have more information to better answer customers’ questions. We immediately bought tickets for a team from Saunders to go to Europe the week before Christmas. My wife was not happy, but it was something we had to do.”

Researcher in Europe showing examples of Boxwood Blight.

Bennett Saunders loading a truck with sample plants for NCSU trials.

Since the disease had been prevalent in Europe since the mid-1990s, members of the Saunders team spent time in Belgium and the United Kingdom to learn tactics to combat it. European researchers mentioned that they had seen that genetic tolerance for the disease varied among boxwood species. Saunders realized that trials could be performed, similar to the Leafminer trials, to discern genetic tolerance. In 2012, Saunders Brothers teamed up with Kelly Ivors at North Carolina State University to begin trialing different boxwood species and cultivars. Thanks to years of collection, many different boxwood cultivars existed at the nursery in Virginia, so Saunders sent samples of these varieties to be part of the trials. This research proved to be so insightful that after the research was completed at NCSU in 2015, Saunders continued the trials privately. It was clear this was a challenge that could be overcome.

Kelly Ivors (middle) and team at NCSU.

NewGen Independence® in field trials.

Since learning about the disease, enormous resources have been dedicated to learning about Boxwood Blight. Saunders Brothers has donated thousands of plants, given input into multiple research projects, and made every attempt to better educate themselves and the growing community about this disease. Teams have traveled domestically and internationally to better understand a disease that many once thought would be the end of boxwood. Working with researchers from state and federal agencies, as well as international groups, the continued message was apparent that through a greater understanding of the disease, the battle with Boxwood Blight will be won with tolerant varieties and best management practices.

NewGen Freedom® in production.

Holding on to that message of hope, and after years of trialing, certain cultivars continued to outperform many of the popular varieties on the market. Two of those cultivars were chosen because they stood out from the rest. “These plants showed up and made us smile and think ‘We’ve really got something here’ that we can share with the industry,” remembers Robert. The discovery of these beautiful plants characterized by their superior resistance to Boxwood Leafminer, high tolerance of Boxwood Blight, and WOW factor in the landscape led to the creation of the NewGen™ brand. You can read more about that story here.

From one 13-year-old boy’s love of a charming little evergreen grew a family business dedicated to innovation and looking for solutions. Saunders Genetics, LLC was created to become a resource for all boxwood enthusiasts for generations to come. With over 70 years’ of experience and a passion for boxwood, they are excited to introduce a new generation of boxwood to the industry.

Paul Saunders and his wife, Tatum, at their home.