For more than 75 years, the Saunders Family has been devoted to boxwood and its development in an ever-changing industry.

Mildred Saunders enjoys her front porch in the 1950s.

On a bright April day in 1947, 13-year-old Paul Saunders joined his mother Mildred as she pruned the English boxwood hedges around the front porch of their home. Even though baseball was Paul’s favorite pastime, he turned down a game with his friends playing in a nearby cow pasture to shadow his mother. Mildred was an enthusiastic gardener and passionate member of the Nelson County Garden Club. Paul had learned how to propagate shrubs from his science teacher and local nurseryman, Mr. Atto. Paul gathered 77 cuttings as his mother snipped and planted them in a nearby patch on the northern side of an eroded hill, a perfect spot with a thicket of pines overhead for shade, and a spring close by for water.

Paul works in one of the first boxwood plantings in the 1950s.

Paul and his mother, Mildred look at boxwood in the garden.

Paul enlisted the help of his friend “Boochie” White to become his partner in the venture. Boochie was responsible for most of the watering because he lived close to the plants. Of those 77 cuttings, 25 rooted and became the genesis of the Saunders family’s commercially grown boxwood nursery.

The following July Paul bought out Boochie’s interest for $1.00 and moved the fledgling nursery to a new location that offered richer soil and a water spigot. Buoyed with the success of the first planting, he then planted 1,000 cuttings of both English and American boxwood. “I could water them daily with a water hose from the spigot at the hen house,” Paul reflected. “My little boxwood nursery became part of my 4-H Home Grounds Beautification project. I stuck more cuttings in rooting beds near an old woodpile. John Whitehead, our County Farm Agent, encouraged me as the nursery grew.” Paul remembers many people asking him, “What are you going to do with all those boxwood?” “I don’t know,” he replied, and went on planting.

Paul Saunders plants boxwood liners in the 1950s.

Year after year, Paul continued to plant more boxwood and as the nursery grew, so did the family. Paul met his wife Tatum in 1955 in Franklin County at a 4-H party. He recalls that on one of their early dates, she helped him strip boxwood cuttings to prepare for planting. They married and eventually welcomed seven sons to their family. The boys (four of whom run the Saunders Brothers nursery today) all have stories of what it was like to grow up on the farm. “If you ate at the dinner table at night, you were expected to be at work the next day at 8 A.M., all days except Sunday,” reflects Bennett Saunders. “No exceptions, even for friends of the family.”

Paul’s wife Tatum checks on some azaleas in the nursery.

Paul plays with sons Massie and Tom.

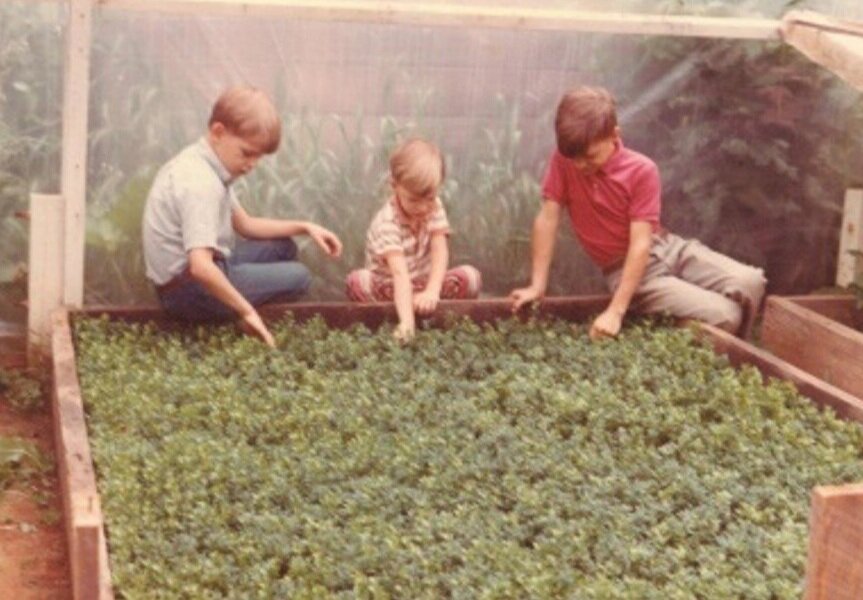

From an early age, the sons participated in every part of boxwood production around the farm. Bennett Saunders, General Manager of Saunders Genetics, remembers, “As kids, we would get paid a penny apiece for each boxwood cutting we stripped and stuck. This is how we would earn our extra spending money.” As the boys grew, they continued to play an essential part in the daily farm responsibilities. “I remember spending most weekday evenings at the nursery loading trucks with boxwood from March to May,” recalls Bennett. “At the time, boxwood were about 40% of the plants we grew.”

Brothers Robert, Bennett, and John check on boxwood cuttings as young boys.

Plants were first marketed locally, but as the nursery grew, boxwood began to be shipped all over Virginia. One day in 1962, Paul received a phone call from the National Park Service, asking to buy 1,500 boxwood. Paul asked where the plants were going, but he was told their destination was confidential. Eventually the word got out that the boxwood were headed to the White House. President John F. Kennedy and his wife Jacqueline had recently returned from an international trip where they were inspired by the formal European gardens and wanted to renovate the White House Rose Garden.

Saunders Brothers boxwood were planted outside the White House in the 1960s.

Those same beds still exist outside the White House today.

The nursery continued to expand to the farm’s fertile river bottoms and hillsides. All was well and sights were set on a bright future until a warm August night in 1969 when Mother Nature threw a monkey wrench in the plan. In less than five hours, through the middle of the night, Hurricane Camille dumped over 20 inches of rain on the mountains of Nelson County, Virginia. The devastation and loss of life in the county were horrendous (1% of the population of the county perished). Mudslides, flooding, and avalanches of debris covered the area. The raging Tye River destroyed nearly 10 acres of Saunders plants and land. Although the damage was devastating, a few boxwood that were planted on higher ground survived. This nucleus gave birth to a container nursery at Tye Brook Farm.

Apple bins were used to load boxwood around.

Although boxwood had been used as a common landscape plant for many years, only two varieties were typically used in landscapes. That changed in the 1970s as boxwood came to face more and more disease problems. Up until this point, most of the boxwood market was made up of English boxwood (Buxus sempervirens ‘Suffruticosa’). As Boxwood Decline became more prevalent, the company began to move towards a wider selection of boxwood cultivars that were more resistant to the disease. Robert Saunders, General Manager of Saunders Brothers remembers, “In the spring of either 1981 or 1982, I was in high school and I got a note from the principal’s office saying I needed to call home. I called and my dad explained that he wanted me to come home to see an experiment he was doing. He was planting a test garden of new varieties of boxwood. At that time, we grew only English and American boxwood, but my dad thought we should try some new ones.” Robert was dumbfounded for two reasons, “Number one, I hated plants, so I did not want to have anything to do with it. Number two, why did we need new varieties of boxwood? Little did I know I would end up working in the middle of it. From those trials, an evolution of perspective began and, we soon found Green Beauty, Green Velvet, Green Mountain and many other varieties. Most importantly it taught us about life beyond our small boxwood world.”

The exploration into new varieties of boxwood began to shed light on another lurking boxwood pest. “There was a field planting of Buxus sempervirens ‘Elizabeth Inglis’ that had just been eaten up with Boxwood Leafminer,” Bennett remembers. “It had never been sprayed and was just covered in blistered leaves.” Deciding this might be something worth exploring, they planted some other varieties near the host plant to see if different cultivars showed any natural resistance to the pest. Early observations showed that there was hope for these different cultivars which encouraged Saunders to pursue more formal research.

A grower in Belgium teaches the Saunders team about Boxwood Blight.

Then, in the fall of 2011, Bennett recalls that, “we began to hear horror stories about a disease called Boxwood Blight which was devastating boxwood nurseries in North Carolina and Connecticut. We called a meeting the Monday after Thanksgiving to decide what to do. We decided we needed to go to Europe before the MANTS show to have more information to better answer customers’ questions. We immediately bought tickets for a team from Saunders to go to Europe the week before Christmas. My wife was not happy, but it was something we had to do.”

Since the disease had been prevalent in Europe since the mid-1990s, members of the Saunders team spent time in Belgium and the United Kingdom to learn tactics to combat it. European researchers mentioned that they had seen that genetic resistance to the disease varied among boxwood species. Saunders realized that trials could be performed, similar to the Leafminer trials, to sort out the resistance. In 2012, Saunders Brothers teamed up with Kelly Ivors at North Carolina State University to begin trialing different boxwood species and cultivars. Thanks to years of collection, Saunders sent samples of these varieties to be part of the trials. This research proved to be so insightful that after the research was completed at NCSU in 2015, Saunders continued the trials privately. It was clear Boxwood Blight was a challenge that could be overcome.

Bennett Saunders loads boxwood headed to NCSU for research.

Since learning about the disease, enormous resources have been dedicated to learning about Boxwood Blight. Saunders Brothers has donated thousands of plants, given input into multiple research projects, and made every attempt to better educate themselves and the growing community about this disease. Teams have traveled domestically and internationally to better understand a disease that many once thought would be the end of boxwood. Working with researchers from state and federal agencies, as well as international groups, the continued message was apparent that through a greater understanding of the disease, the battle with Boxwood Blight will be won with tolerant varieties and best management practices.

“Thomas Edison once said “I have not failed. I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.””

Holding on to that message of hope, and after years of trialing, certain cultivars continued to outperform many of the popular varieties on the market. Two of those cultivars were chosen because they stood out from the rest. “These plants showed up and made us smile and think ‘We’ve really got something here’ that we can share with the industry,” remembers Robert. The discovery of these beautiful plants characterized by their superior resistance to Boxwood Leafminer, high tolerance of Boxwood Blight, and WOW factor in the landscape led to the creation of the NewGen™ brand.

Brothers (left to right) Jim, Tom, Bennett, and Robert with their father Paul (center) at the Rose Garden renovation reveal at the White House in 2020 where Saunders Brothers provided the boxwood for the renovation.

From one 13-year-old boy’s love of a charming little evergreen grew a family business dedicated to innovation and looking for solutions. Now the next generation of Saunders are poised to move into the future. Saunders Genetics, LLC was created to become a resource for all boxwood enthusiasts for generations to come. With over 70 years’ of experience and a passion for boxwood, they are excited to introduce a new generation of boxwood to the industry.