“Let’s zoom meet.”

This is a second nature saying to us now. We hear it every day, but one year ago, somebody would have thought you needed counseling if you made that comment! Necessity is the Mother of Invention. In this pandemic time teleconferencing has filled a critical need and changed the way we communicate in our businesses– perhaps permanently.

Necessity as the Mother of Invention for boxwood

COVID-19 has required extra precaution from workers in all tasks

Decades ago, nurseries had boxwood that would survive the winter, but they were ugly! ‘Green Velvet’, arguably the most planted boxwood cultivar in the United States today, was developed by Sheridan Nurseries in Canada as an answer to the poor Winter performance and appearance of boxwood in Canada and the Midwestern United States in the 1960s.

Sheridan Nurseries’ ‘Green Velvet’ opened doors for boxwood in colder climates

Necessity being the Mother of Invention, Sheridan crossed Buxus sinica var. ‘insularis’ with a Sempervirens cultivar. The thought was that the ‘insularis’ would offer cold hardiness and the Semperviren cultivar would give the boxwood aesthetics. Four hybrid offspring were chosen including ‘Green Velvet’, ‘Green Mound’, ‘Green Mountain’, and ‘Green Gem’, all of which are still in widespread production 50 years later. These plants revolutionized the nursery industry in the colder climates of the United States and Canada. Boxwood were suddenly a popular plant in these colder climates.

In 2011, the first confirmed cases of Boxwood Blight were found in North Carolina and Connecticut. Boxwood Blight devastated whole fields of plants in the humid and wet mountains of the Southeast. Saunders Brothers, Inc. knew that their existing boxwood variety makeup would not survive the pressures of Boxwood Blight.

NewGen Independence® raises the bar for Boxwood Blight resistance

Again, Necessity is the Mother of Invention. Within a few years, NewGen Freedom® and NewGen Independence® were introduced as answers to the problems the growers faced. Not only has NewGen® addressed the problems with Box Blight, but also with Boxwood Leafminer, a pest that was particularly a problem with the Sheridan hybrids.

So where do we go from here?

NewGen Freedom® and NewGen Independence® only fill a small part of the artist’s boxwood palette that are needed in North America.

We need more shapes and sizes of boxwood, but with the Box Blight resistance and Boxwood leafminer resistance. By continuing to evaluate existing cultivars, as well as newly bred cultivars, our hopes are to have an upright plant, a variegated boxwood, and a dwarf plant soon. And that’s just the beginning.

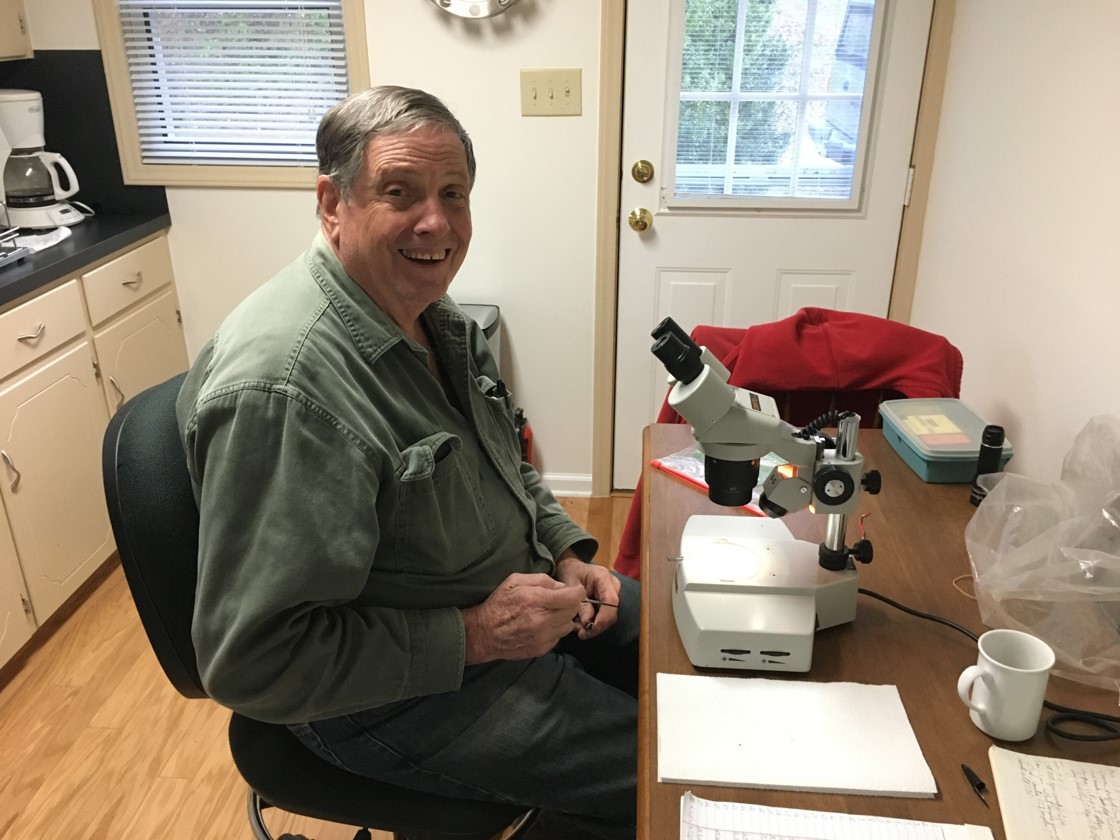

Bennett Saunders of Saunders Genetics oversees trials and evaluations for promising future introductions for NewGen® Boxwood

NewGen® is also focusing on cold hardy boxwood. The Sheridan varieties ‘Green Velvet’, ‘Green Mountain’, ‘Green Mound’, and ‘Green Gem’ have historically been the most cold-hardy plants. Mike Yanny, a seasoned boxwood breeder in Wisconsin, agrees that ‘Green Mound’ and ‘Green Gem’ are Zone 4 plants, but ‘Green Velvet’ and ‘Green Mountain’ are not reliable Zone 4 boxwood. In addition, all four of these cultivars show moderate susceptibility to Boxwood Blight and extreme susceptibility to Boxwood Leafminer, particularly in areas warmer than Zone 5. We can do better. NewGen® is very focused on finding cold hardy cultivars which would thrive in Zones 4-5.

The future is ‘cold’ for NewGen® Boxwood!

Who knows what boxwood problem will come next? Another disease? Another insect? We see light at the end of the Boxwood Blight tunnel and we know not what the future holds. But rest assured that we will attempt to tackle any boxwood challenge before us.

Happy Spring!