Adult females deposit fertilized eggs through the underside of the tender new boxwood leaves.

Although boxwood are known for their low maintenance and tend to have few pests, Boxwood Leafminer (Monarthropalpus buxi) can be a challenge for growers in the Mid-Atlantic region and around the United States. Technically a midge, not a leafminer, this pest causes damage that starts small as discolored leaves but can become severe as populations build over a period of years. Luckily, this tiny orange insect has only one life cycle per year, providing easy and effective ways to treat it.

The life cycle begins in the early spring as the previous year’s larvae pupate and cause the boxwood leaves to discolor, blister and swell. Those pupae emerge as adults in April/May (in central Virginia), hovering only inches above the boxwood due to their weak flying abilities. Over an approximately 3-week period, adults emerge in waves to mate. Females then complete their life cycle after they lay eggs in the tender underside of the new boxwood leaves. These eggs hatch in early summer (mid-June in central Virginia) and the larvae begin the cycle of growth that will conclude the following spring.

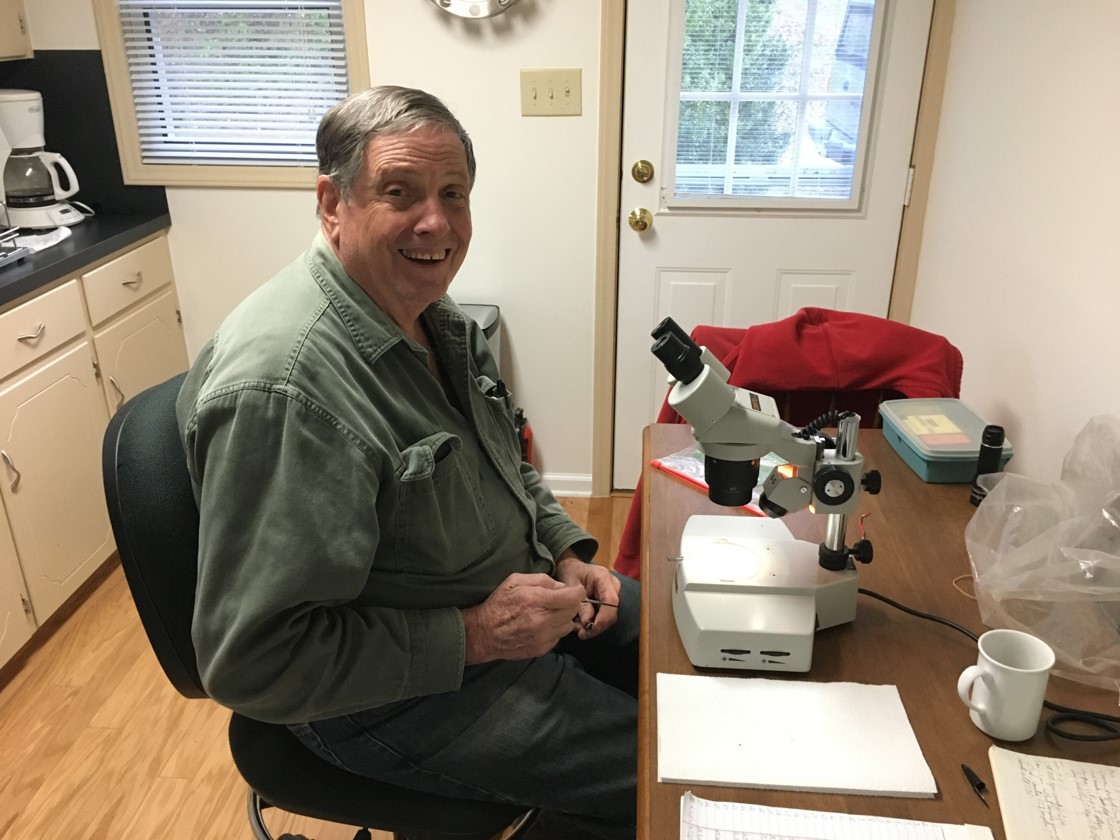

Photo taken July 1: The young Boxwood Leafminer larvae are only visible under a microscope.

These early instars are very small, see them here compared to a pin head.

Chemical controls are the best alternative for complete treatment of Boxwood Leafminer. It is unnecessary to time a chemical application that successfully kills Boxwood Leafminer adults because the adults emerge over several weeks and live only several days, requiring multiple sprays. The larval stage provides a much longer spray window and is likely to be significantly more effective. The eggs hatch around mid-to late June in central Virginia, and the larvae are eating and growing, during the summer and fall. Research has found systemic insecticides to be effective in killing larvae until temperatures turn cold, which in some years is not until late October or early November. This strategy can provide control for up to 2-3 years as a thorough spray totally wipes out the population.

Severe blistering and discoloration are the result of heavy Boxwood Leafminer populations.

Boxwood Leafminer adults are small, orange, mosquito-like midges, that are often found hovering only inches from the foliage because they are weak flyers.

For Boxwood Leafminer control, growers have had excellent success with products in the neonicotinoid group that contain the active ingredient imidacloprid, thiomethoxam, or dinotefuran. There is a great deal of ongoing discussion regarding neonicotinoids and other chemicals and their possible effect on pollinators. Nurseries and gardeners should follow good science and alternative methods to control these pests to further eliminate use of this group of pesticides. All growers should minimize the use of any pesticide by practicing Integrated Pest Management or IPM. The goal of IPM is to effectively control a pest while minimizing negative impacts on pollinators, the environment, and employees.

Examples of insecticides listed in the Virginia Tech Nursery Crops Pest Management Guide are thiamethoxam (Flagship 25WG at a rate of 6 oz./100 gallons of water) or dinotefuran (Safari SG ¼ to ½ lb. / 100 gallons of water). These systemic products are absorbed and dispersed throughout the plant. Only one application a year is necessary to target the larvae feeding within the leaf. In central Virginia, it is recommended that the application takes place late June through mid-October.

To be noted: While Saunders Genetics has worked with nursery growers who have successfully used the pesticides listed above, no guarantees or promises, nor any opinions concerning the effectiveness or safety of these or any other pesticides are made. Always read the labels and other product information from the manufacturer and discuss the proper use and application of products with appropriate company representatives or acknowledged experts.

Although chemical control is an option on susceptible cultivars, there are also many boxwood varieties that have shown genetic resistance to Boxwood Leafminer. This genetic resistance is a defining feature in the NewGen™ Boxwood program where the goal is to provide grower-friendly plants that can thrive when faced with pest and disease pressure. NewGen™ boxwood were chosen for the program because they are more resistant to Boxwood Leafminer than most varieties currently on the market. If you are replacing or planting boxwood, consider NewGen™ varieties so that costly and troublesome sprays will not be necessary.